Multilingual Abusive Comment Detection in Indic Languages - Thoughts and Progress

Published:

On my submission for the Moj Multilingual Abusive Comment Identification - Challenge

Note: As a beginner in NLP, and a complete novice in Kaggle-style competitions, my progress, and subsequently this blog, has been shaped by the code and discussion sections on the competition page, and especially the work of Harveen Singh Chadha.

I came across the workshop/competition on Linkedin in late Aug 2021. What grabbed my interest was the chance to get some hands-on NLP experience, something I’ve been meaning to do for a while now. What cinched my interest was the fact that the top performing teams get the chance to interview at ShareChat. While I had no illusions of coming close to winning, the opportunity was too good to pass up.

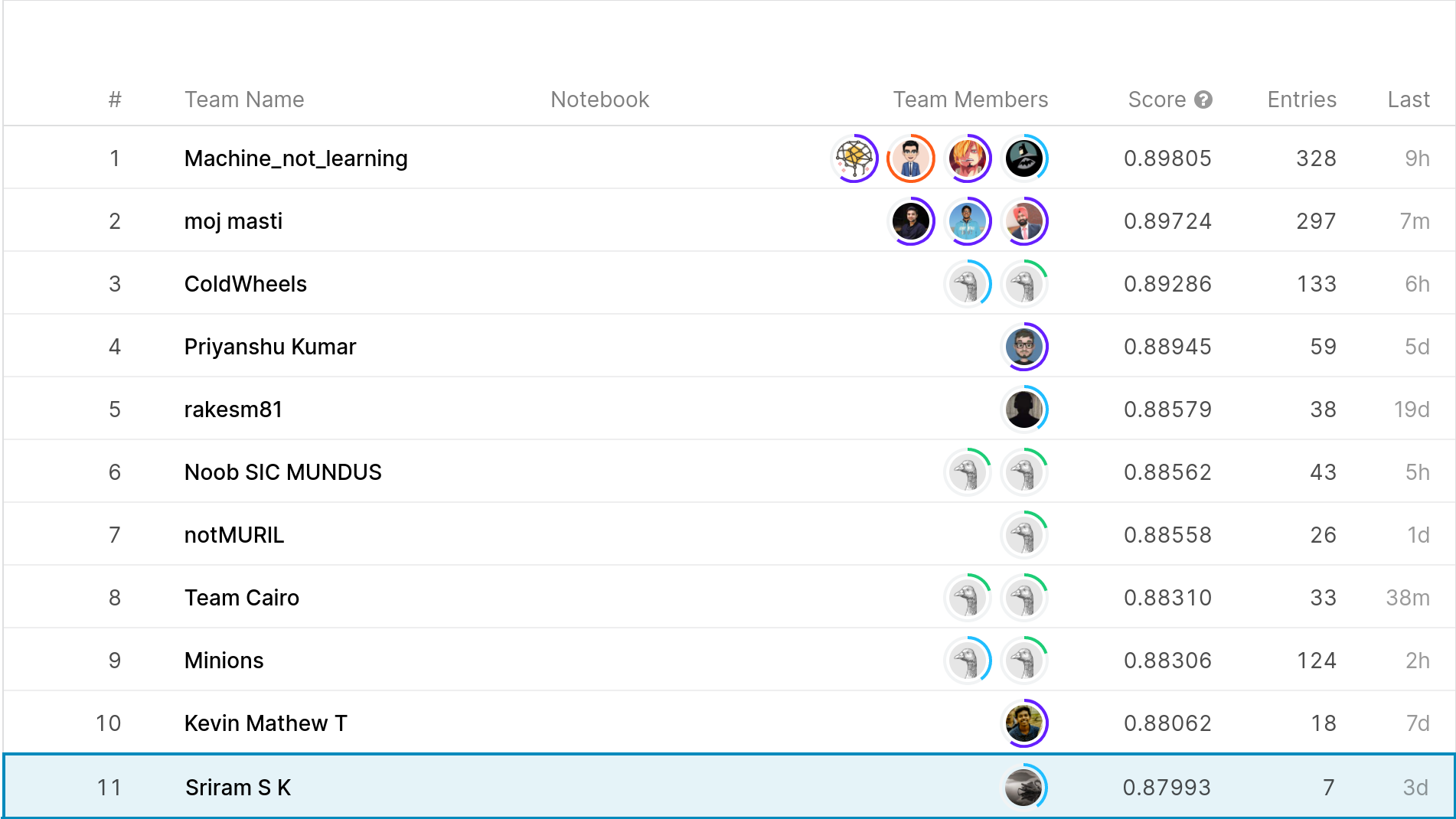

In this post, I’ll be describing my approach towards the problem, the augmentations which got me the dubious distinction of being 11th on the leaderboard (Oct 15 2021). Code is available on GitHub

Overview

The Moj Multilingual Abusive Comment Identification - Challenge is a competition organized as part of the 2nd Workshop on Emerging Advances in Multimodal AI workshop at BigMM 2021, organized by ShareChat and the MIDAS lab at IIIT-Delhi (where I’m a Research Assistant!). The challenge is geared towards detecting abusive comments made on ShareChat’s short video app, Moj. A key feature of ShareChat and Moj is that their applications are regional, having content only in regional (Indic) languages, notably not containing English as an option. The dataset provided is large (660k+ records) and diverse (13 languages from across India), with each record containing the comment text, a binary label marking whether it is abusive, and additional comment/post metadata.

Positions on the leaderboard are determined by the F1 score of the submission, weighting both precision and recall. In this context, low precision would cause additional work for human moderators who would have to correct wrong predictions, or cause accounts to be punished unfairly if the process is automated. On the other hand, low recall would mean that the abusive comments are running wild, so to speak. Both undesirable outcomes to say the least. As can be seen on the leaderboard, competition is fierce, with a couple of percentage points separating the top performers from the 15th(!), with about a 1000 submissions between them. And with that introduction, let’s dive into what I did.

MuRIL + demoji [F1 -> 87.701]

Fortunately for me, a starting point was very clearly laid out. Thanks to Harveen’s notebook, I had access to a high level Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), code with the huggingface transformers library which I was new to, a tokenization pipeline, and some baseline results to compare my own implementation against.

It wouldn’t be much of a learning experience if I used the same code, and my framework of choice was PyTorch anyway, so I decided to re-implement the approach in PyTorch, more specifically, PyTorch Lightning for its excellent abstractions. Lightning allows cleanly separating parts of the code into modules (model, dataset, trainer) wrapped into a well-documented API. Monitoring the model was accomplished with wandb which provides a great dashboard for visualizing progress.

The model used was MuRIL, a BERT-based model trained on indic languages only. It has been trained on corpora of 16 indic languages (including Hindi, Kannada and even Sanskrit!), and English. Furthermore, a factor which elevates MuRIL above other models is the fact that its training corpus was augmented with transliterated data, which is very apt for this scenario. Multilingual speakers often exhibit a phenomenon known as code-switching/mixing, where they combine multiple languages when conversing with each other. This is of course very common in India, even garnering names such as Hinglish, Kanglish etc. In text, there is also script-mixing, when the scripts of different languages are combined (Devanagari for the Indic languages and Roman for English). Opening a few family WhatsApp groups should be enough to convince the readers that Indian text is both code-mixed and script-mixed in nature. For illustration, consider the following sentence, a battle-cry of Kannadiga cricket fans:

ಈ ಸಲ cup namde 🏆 (This time, the cup is ours)

Slightly contrived perhaps, but this text includes elements written in Kannada in the Devanagari script, English, code-switched Kannada and an emoji to boot. For a machine learning system to moderate the language of the common man, it must understand the language of the common man in all its code-switched, script-mixed, emoji-filled glory. Which brings me to the second augmentation of my first attempt, handling emojis. In another notebook by Harveen, he mentions that mostly emojis are not known to the tokenizer, which makes sense as MuRIL has been trained on data extracted from CommonCrawl and Wikipedia, not likely to be rich sources of emojis. Emojis however, can be indicators of abusive comments. For a crude example, I have a hunch that ![]() would have a strong correlation with abusive comments.

would have a strong correlation with abusive comments.

As for how to handle them, quite simple. Just replace the emoji with its descriptive text with demoji, giving us more information to work with and potentially helping our model flag words like “Aubergine”. This concludes the methods involved in my first approach, namely re-implementing the components around using MuRIL in PyTorch Lightning, and integrating demoji into the pipeline by replacing emojis with their descriptive text.

Free Lunch Appetizer with MC Dropout [F1 -> 87.760]

At MIDAS, I recently explored uncertainty estimation and calibration in neural networks, and the methods involved in reducing a model’s overconfidence. One such was Dropout as a Bayesian Approximation by Gal and Ghahramani, a well known paper introducing the concept now popularly known as Monte-Carlo Dropout or MC Dropout. Without going into much detail, as there are better resources available, MC Dropout simply involves turning on Dropout at prediction time, and making multiple predictions and averaging over them. It’s easy to implement, is architecture independent (as long as the model contains Dropout) and can be easily plugged into already trained models. If Dropout is like training a virtual ensemble of models, MC Dropout is like predicting with a virtual ensemble of models.

To implement, all that needs to be done is to iterate over the model’s layers, and to switch the mode of the Dropout layers to train to switch them on. The test predictions for a single batch are computed multiple times and then averaged. While the time for prediction becomes much longer, especially with large language models, it still promises increased performance for little to no human effort. In this case, the increase was minimal, scoring only 0.06 points above the baseline.

Going beyond text [F1 -> 87.836]

Up to this point, I had only been considering text and neglecting the other features proided, the metadata which included likes and reports on a comment, as well as the post as a whole. Needless to say, this can be very valuable information. Leveraging the community in moderation can be useful and help in detecting abusive comments. As seen on this discussion, there was an inconsistency in metadata, with comments from the same post having varying report_count_posts and like_count_post, which was explained by the fact that the data was gathered over a period of time. To rectify this, I modified the post metadata of each comment of a post to be equal to the maximum of the report/counts on that post. My rationale came from my past usage of Moj, which has been carefully designed to have a clean, straightforward UI. In particular, I remember being unable to locate a post I had seen previously, leading to my hunch that the maximum values were from the latest timestamps, and being the latest timestamps, were most representative of the post.

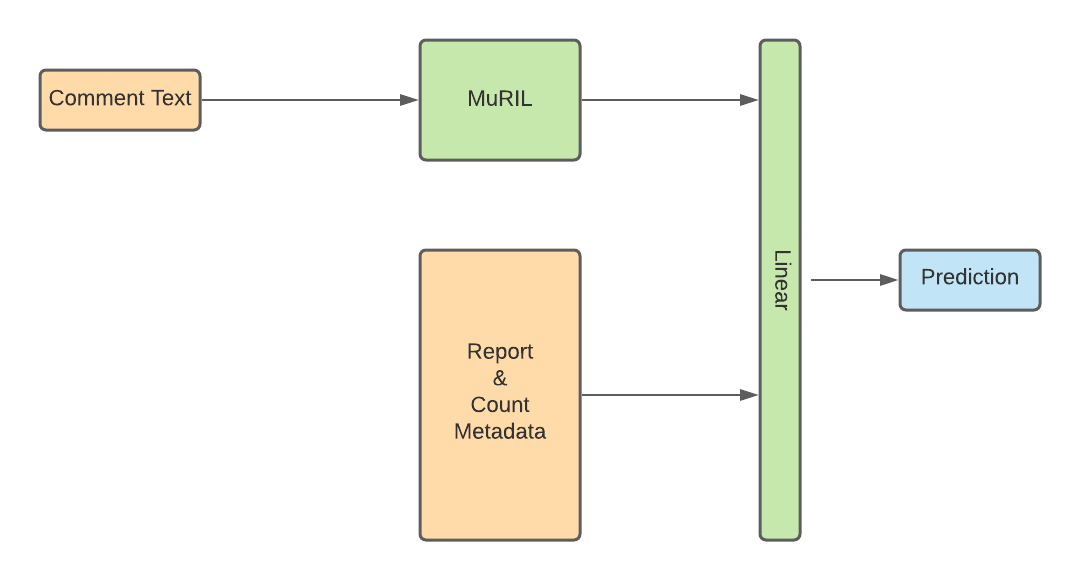

I now had 4 additional features to integrate into the model (reports and likes at the post and comment level). I did so in the form of a simple late fusion, adding a linear layer on top of MuRIL and feeding its prediction along with the 4 other features before making the final prediction.

Models that work together, win together [F1 -> 87.993]

At this point, while I had ideas I wanted to explore (more on that below), I didn’t have the bandwidth to try implementing them, nor did they hold any guarantee of actually working. In a last bid attempt at climbing the leaderboards, I fell back to a tried and tested method: model ensembles. General consensus appears to be that ensembles dominate Kaggle competitions and I have no reason to believe this competition will fare any different.

There are many ways of ensembling models, varying in complexity leading up to a meta-learner trained on the predictions of other models. I stuck with the most basic form of an ensemble, voting. Every model is given equal weight, and the mode of their predictions is taken as the final prediction. There are of course numerous problems with voting, mainly that every model is given equal weight and is implicitly assumed to be equally qualified.

“The best argument against Democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter.” – (falsely attributed to) Winston Churchill

The additional models in consideration were mBERT and indicBERT, both BERT-based models. mBERT or multilingual BERT is trained on the 104 largest languages by Wikipedia size, whereas indicBERT has been trained on a specially gathered indic language corpus by the folks at indicNLP. In training, they performed slightly worse than MuRIL, bolstering my decision to go ahead with the voting ensemble, rather than a more complicated meta-learner. The ensemble did surprisingly well, compared to the effort that went into creating it.

Closing thoughts, avenues to explore

These were the approaches I tried in crafting a model that could score well on the abusive comment detection task. The top performing teams have clearly put in incredible effort (300+ submissions!) and consist of Kaggle Experts and Masters. Nonetheless, I’m fairly happy with my performance as a novice, and that each of these augmentations provided a boost in performance. I’d encourage anyone who’s dipping in their toes in NLP to try their luck at a Kaggle competition, to draw from existing notebooks, pursue hunches and explore in general. In particular, Indic NLP seems to me to be a more complex form of NLP, due to the massive diversity in our country. IndicNLP, and its parent AI4Bharat have some fantastic resources that should quickly enable getting started with applying NLP for Indian languages. Now, the solutions that I’d like to explore in the future:

- Handling low resource languages -> The diversity inherent in the Indian subcontinent means that we cannot procure very large corpora for many of our less popular languages. While the dataset provided by Moj contains text in Haryanvi, Bhojpuri, Rajasthani, none of the models have been trained on corpora including these languages. Thus far, I have assumed that the model will perform relatively well on these languages due to their similarity with Hindi, but that is simply an assumption. A more rigorous look at this is necessary. Exploring the model’s performance stratified by language will provide insights into where performance is weak, and addiional measures can be taken. For example, utilising a separate model for Bhojpuri comments using dedicated Bhojpuri data.

- FastText -> While describing the language of the common man earlier, there is one other facet which I did not describe. Misspellings. In the casual context of a comments section, there are bound to be contractions, alternate spellings and misspellings. While large language models can be robust to misspellings given a large text corpora, I do not believe that this has been explored from a multilingual code-switched script-mixed viewpoint, where the potential for misspellings of a given word increases exponentially. FastText embeddings are based on combining sub-words, and have been used to correct spelling mistakes. IndicNLP provides IndicFT, embeddings for Indian languages and mention that they are highly effective due to their highly agglutinative morphology. However, they provide monolingual model/embeddings for 11 indic languages and not a single multilingual one, which would be most apt for this task. The final piece of the puzzle is MUSE: Multilingual Unsupervised and Supervised Embeddings, providing FastText embeddings aligned in a common space. While this may not prove to be better than the best performing models/ensembles (an F1 score of nearly 90% is a high bar to cross), I think this is a novel solution worth exploring.

Feel free to contact me if you have any questions!