FrLove : Could a Frenchman rapidly identify Lovecraft?

Published:

FrLove : Could a Frenchman rapidly identify Lovecraft? (This post was submitted to ICLR Blogpost Track 2022 and was rejected. The submission is replicated here.)

This post examines the work in Self-training For Few-shot Transfer Across Extreme Task Differences, accepted as an oral presentation at ICLR 2021. In this post, we break down the task of cross-domain few shot learning, present a bird’s eye overview of the techniques involved, and describe the proposed method - STARTUP. In the latter section of the post, we also attempt to extend the experiments to language. To the best of our knowledge, cross-domain few shot learning in a multilingual setting has not been explored before and it raises interesting questions. Our code is available at this link.

What is STARTUP?

“Self Training to Adapt Representations To Unseen Problems”, or STARTUP, is a simple but highly effective method that tackles the problem of cross-domain few shot learning. Few-shot Learning is the task of learning on a very limited set of samples. For example, 5-shot learning implies that there are 5 examples (shots) available for each class that the model is supposed to learn. Typically, we have a large training set and much smaller support and query sets. The training set is composed of base classes, and the support set contains the target classes to be learnt by the few-shot learner.

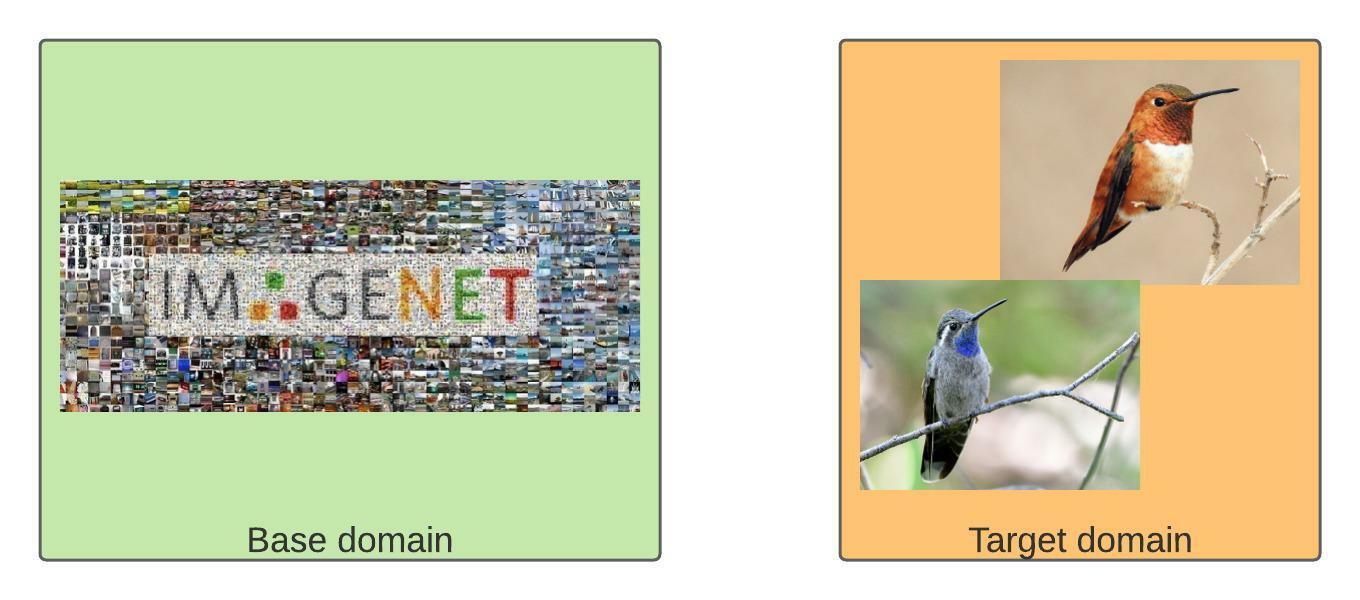

In conventional few-shot learning, a key observation is that there is a relation between the base and the target domains. For example, the base domain may be ImageNet (containing many bird classes), and our target domain may be the various species in the hummingbird family.

Figure 1: ImageNet may not contain images of the Rufous Hummingbird or the Blue-throated mountaingem, but it does contain many bird classes, including ‘hummingbird’ itself.

Figure 1: ImageNet may not contain images of the Rufous Hummingbird or the Blue-throated mountaingem, but it does contain many bird classes, including ‘hummingbird’ itself.

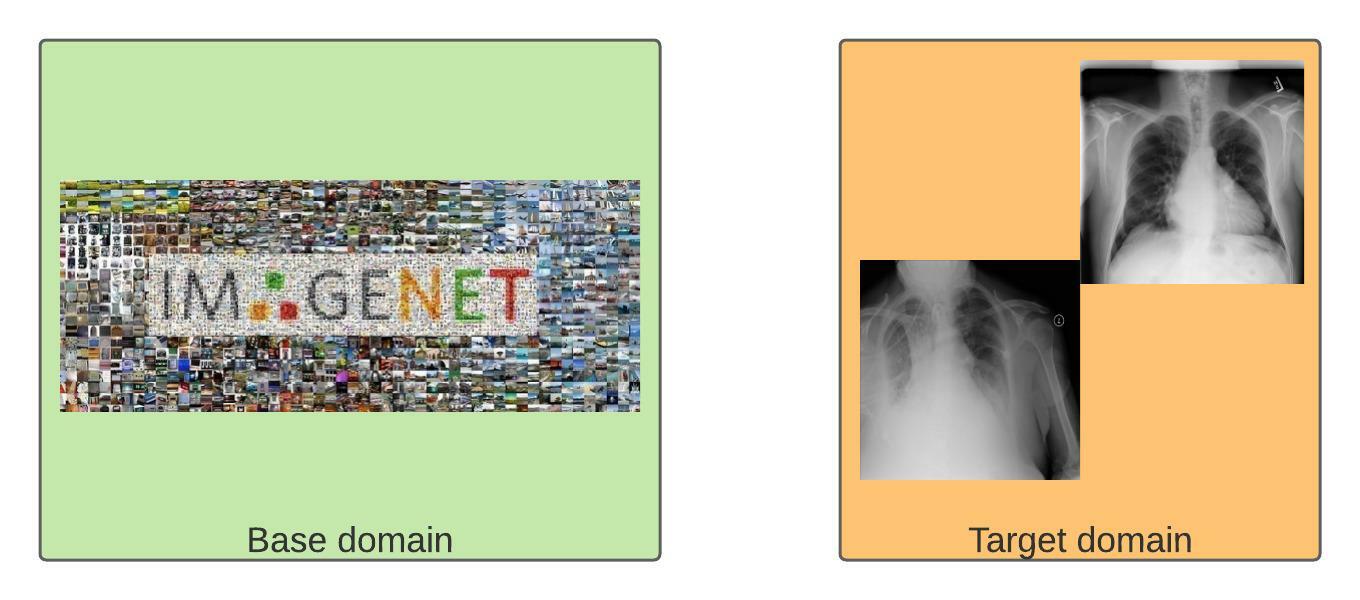

Upping the difficulty, we have the task of cross-domain few shot learning, where in addition to learning from a very limited number of examples, we must also contend with the fact that our source and target domains are radically different. Such as going from distinguishing between objects to detecting possible pneumonia. Recent work has shown that the performance of few-shot learning methods degrades when confronted with this extreme task difference.

Figure 2: As diverse as ImageNet is, it does not contain X-ray scans (yet). Images from ChestX dataset

Figure 2: As diverse as ImageNet is, it does not contain X-ray scans (yet). Images from ChestX dataset

What is the motivation for this task? As the readers might be aware, collecting high-quality data can be expensive, time-consuming, and prone to dangerous biases. The promise of few-shot learning, i.e. learning with a few well-labeled examples, then becomes very attractive. Cross-Domain Few Shot Learning (CD-FSL) takes this promise further, by now removing even the barrier of having semantically related base and target domains.

The authors’ key observation comes from making use of unlabeled data. Undiagnosed X-ray scans and unlabeled satellite images are much more readily available than high-quality annotated data and offer an alternative solution in the form of Self-supervised Learning (SSL). SSL has been used to great effect in recent years, especially in the training of large language models. However, SSL requires an incredibly large amount of data to train effective representations. The largest language models today are trained on corpora containing a significant chunk of data on the World Wide Web, such as The Pile. In summary:

- Collecting data for some domains (medical scans, satellite imagery etc) can be hard, time-consuming and difficult. Existing few shot learners are unable to generalize from other domains to these.

- While unlabeled data may be available for these domains, it is not available in the massive amount that is required to train an effective self-supervised representation.

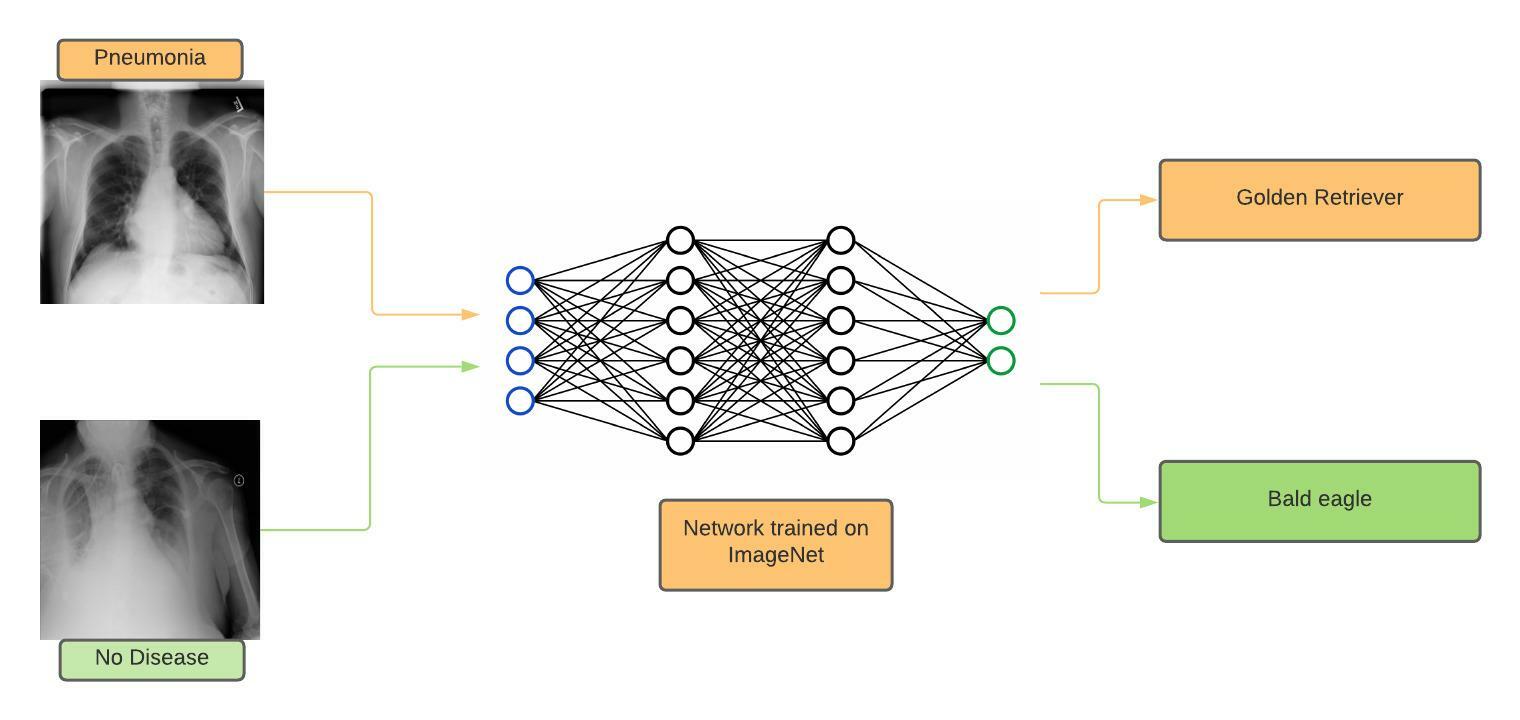

The authors propose STARTUP to leverage unlabeled data in training representations to adapt to the target domain. When a classifier trained on the base domain is applied to the target domain, the classes assigned may be irrelevant, but the grouping in these classes can be utilized to train better representations. Training in this manner would adapt feature representations to the target domain while maintaining the knowledge that caused this meaningful grouping. Put simply, classifying X-ray scans as various ImageNet classes may not be meaningful, but the grouping of pneumonia under the golden retriever class can provide useful information.

Figure 3: In this oversimplified example, we see a network classifying X-ray scans into ImageNet classes. This image depicts a scenario where X-ray scans of the ‘pneumonia’ class are tagged as ‘golden retriever’ by the network, and ‘no disease’ as ‘bald eagle’.

Figure 3: In this oversimplified example, we see a network classifying X-ray scans into ImageNet classes. This image depicts a scenario where X-ray scans of the ‘pneumonia’ class are tagged as ‘golden retriever’ by the network, and ‘no disease’ as ‘bald eagle’.

The model itself labels the data in the target domain, similar to a form of learning known as self-training. In self-training, the model labels its own training data based on its current state. The new labels, which are probability distributions over the classes rather than a single concrete class, are known as pseudolabels. These pseudolabels are then used to train the model and subsequently improve the pseudolabels, in an iterative process. In the case of STARTUP however, the goal is not to improve the model, but to use these pseudolabels to adapt its representations to the target domain.

To reiterate, data from the target domain is classified in the base domain. At the individual level, this classification may not make sense, but at the aggregate level, the distribution of the target data in the base domain can be used to improve the representations learnt. A way to startup better representations, if you will.

How (well) does STARTUP work?

At its core, STARTUP is effective in its simplicity and comprises of three steps in adapting the feature backbone.

- The first step is to learn a teacher model $\theta_T$ which can aid in self-training representations. This model is trained in a standard supervised manner on the base dataset $D_B$ using the Cross-Entropy Loss $\mathcal{L}_{CE}$.

- The teacher model $\theta_T$ is used to softly label the unlabeled data from the target domain $D_U$ to give us the pseudolabeled dataset $D_{U*}$. These pseudolabels are a probability distribution over the classes in the base domain.

- Finally, a student model $\theta_S$ is learnt using $D_B$, $D_U$ and $D_{U*}$ according to the following loss function:

The loss function is made up of three components, each directing learning in a different way. \(\mathcal{L}_{CE}\), as mentioned above, is just Cross-Entropy loss on the base dataset. $\mathcal{L}_{KL}$ is the KL Divergence between the output of the student model and the pseudolabel generated by the teacher, capturing the distance between the two distributions. Together, these two components guide the student to generate groupings of the data similar to the teacher. In particular, the authors posit that minimizing the distance between the pseudolabels of the teacher and the student with KL Divergence encourages the model to emphasize the groupings of the pseudo labels.

Finally, the third component $\mathcal{L}_{SSL}$ is the self-supervised loss on the unlabeled data. In STARTUP, the SSL used is SimCLR, a popular contrastive loss. Very briefly summarized, it minimizes the distance between two augmentations of the same image while maximizing its distance from the other images in the batch. As mentioned earlier, SSL alone requires large amounts of data to train effectively but it boosts STARTUP by extracting meaning from the unlabeled data available.

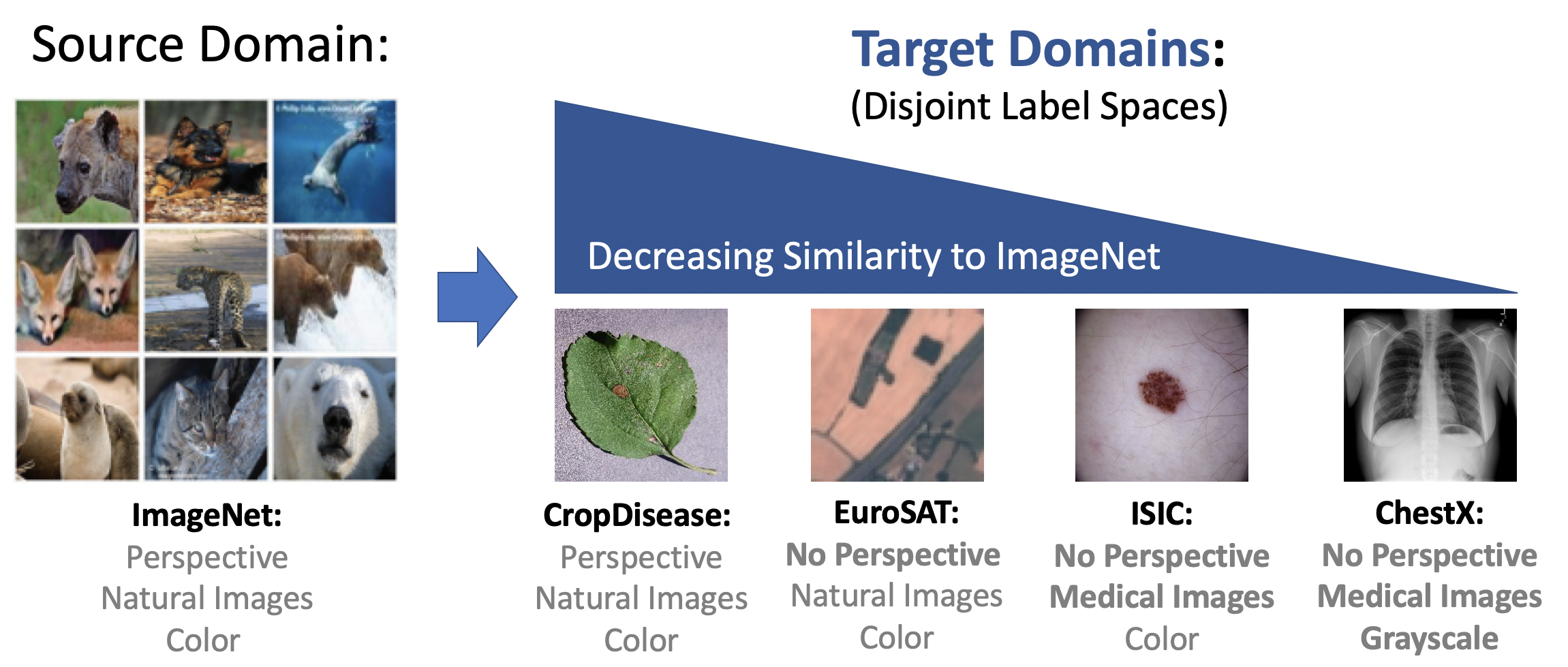

STARTUP fuses multiple paradigms (self-training, self-supervised learning and traditional supervised learning) in a simple fashion to train models that outperform the state-of-the-art on the BSCD-FSL dataset.

Figure 4: The BSDCD-FSL benchmark consists of ImageNet as a base domain and 4 very different target domains. Note the factors which denote the task ‘distance’ (Perspective, content and colour of image). Image from BSCD-FSL

Figure 4: The BSDCD-FSL benchmark consists of ImageNet as a base domain and 4 very different target domains. Note the factors which denote the task ‘distance’ (Perspective, content and colour of image). Image from BSCD-FSL

Results of STARTUP have been omitted in the interest of brevity. In the paper, the authors conduct numerous experiments and ablation studies verifying the effectiveness of STARTUP and achieve an absolute improvement of 2.9 points on average on the BSCD-FSL dataset.

Could a Frenchman rapidly identify Lovecraft?

This section of the post takes a different approach to evaluating STARTUP, namely, evaluating few-shot cross-domain learning when the domains are languages. This raises some interesting questions on the nature of domains and how one might adapt cross-domain learning to a multilingual setting. These experiments are summarized as ‘FrLove: Could a Frenchman rapidly identify Lovecraft?’. Or in other words, could a model which has been trained on French texts (a “Frenchman”) perform few-shot classification (“rapidly identify”) on a text from a different domain (the works of H P Lovecraft, a prominent English author). FrLove is an attempt to answer two questions, one specific to STARTUP and one examining the broader field of cross-domain few shot learning.

- How does the ratio of base classes to target classes affect STARTUP? As described above, STARTUP works by exploiting the grouping of the target domain data among the base classes. Our hypothesis is that the more fine-grained this grouping is, the easier it is for STARTUP to train. Consider a dataset with $n_{base}/n_{target} = 20/10 = 2$. The 10 target classes will be distributed among the 20 base classes, providing more information to STARTUP as compared to $n_{base}/n_{target} = 20/40 = 0.5$. Will the performance of STARTUP degrade when there is ‘crowding’ of the target data in the base classes?

- How can we quantifiably evaluate the distance between domains? This is, of course, a much larger question which cannot be adequately answered within the scope of a blogpost. Nevertheless, we attempt to do so for language by utilizing existing linguistic knowledge.

On the “distance” between languages

The dataset used in the experiments in the paper, the BSCD-FSL benchmark contains 4 datasets, from vastly different domains (see figure above). These datasets are ordered by similarity to ImageNet by a number of heuristics. These heuristics however, are not applicable to any two image datasets of varying contents. We believe it is an important research question to quantify the “distance” between any two tasks in cross-domain learning. One such use case this enables is the efficient transfer of knowledge across domains, since we would be able to gather a sufficient amount of data based on the “distance” between the two domains. In this post, we use language family trees as a universal distance framework.

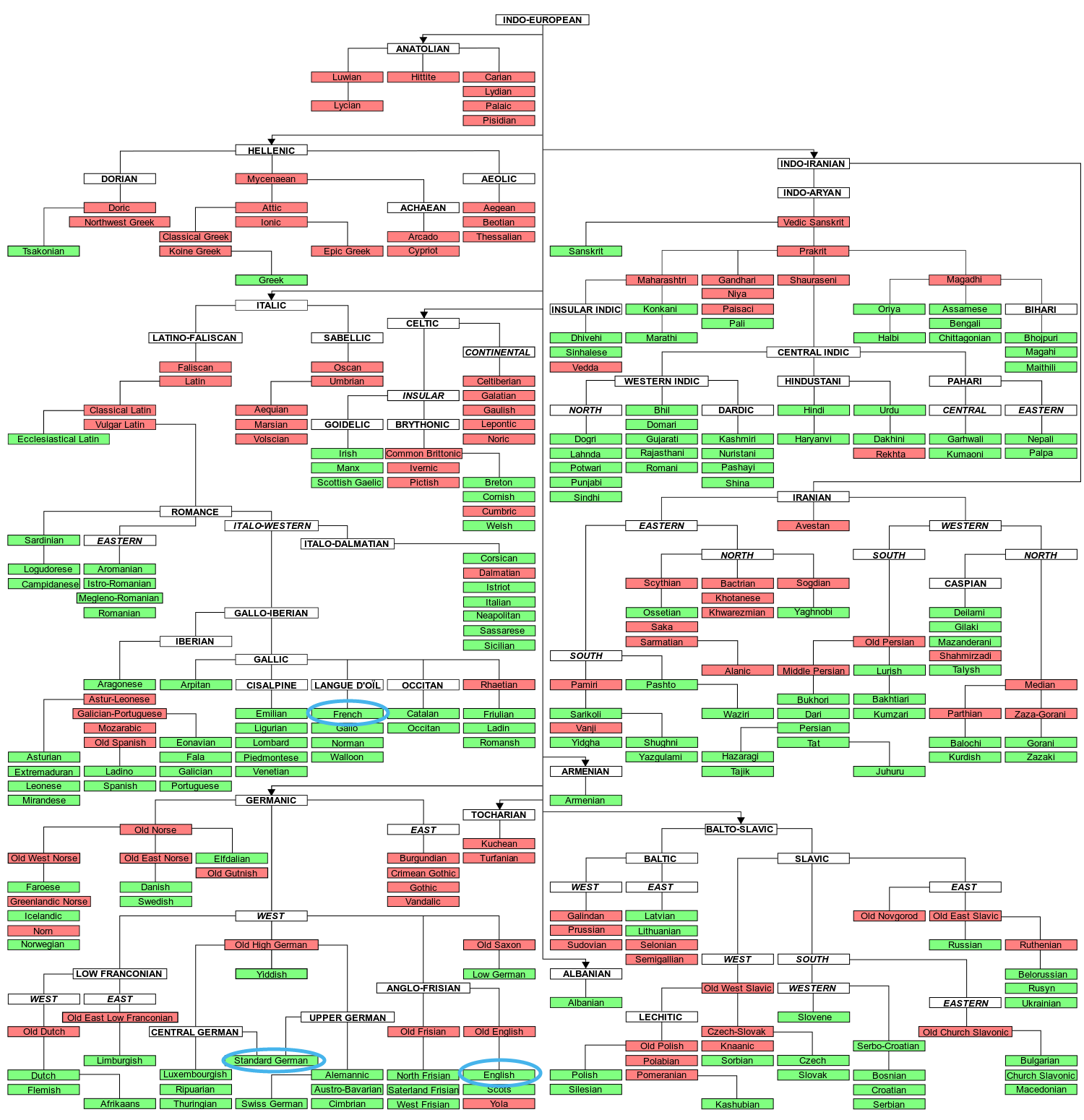

Figure 5: The Indo-European language family tree. Note the highlighted locations of German, English and French. Source

Figure 5: The Indo-European language family tree. Note the highlighted locations of German, English and French. Source

The Indo-European language family comprises of a large number of languages stretching from Europe to Northern India. 3.2 billion people across the world speak one of these languages as their first language. All the languages in this tree are thought to be descended from a single language, called Proto-Indo-European. Through a study of how languages have evolved, their shared innovations and historical evidence, linguists and historians categorize languages into trees and subtrees. In the family tree above, note that German and English belong to the Germanic family tree, whereas French belongs to the Romance family of languages, a separate offshoot. As a rudimentary metric, the distance between the nodes of the tree can give us the distance between the two languages. English and German are closer to each other than English and French which in turn is closer than English and Mandarin Chinese (belonging to the Sino-Tibetan language family).

We hypothesize that performance will be better when transferring from German -> English, as compared to French -> English.

Note: The BCSD-FSL benchmark targets cross-domain learning where the domain is a task, i.e. crop disease classification or satellite image classification. In this section, we focus on the language as a domain. We attempt to quantify the distance between French and English, and not the distance between - for example - French poetry classification and English spam detection, a much harder problem.

Implementing FrLove

In image tasks, even if the domain of the tasks is vastly different (X-ray scans and crop diseases), the basic building block of the image is the same, that is, the pixel. This does not exactly hold true when dealing with languages. The basic element of a written language, the letter, is only common for a script, which vary across languages. For example, in the Indo-European family tree - German, French and English use the Roman script, based on the familiar 26 letters A-Z. In another branch of the tree, Hindustani, the Hindi language uses the Devanagari script (देवनागरी). Thus, we require two languages of the same script but distinct from each other.

Even if two languages have the same script, there is the additional complication that commonly used neural networks like BERT operate at the word or token level. While there may be words in common between languages, we would no doubt see sequences of meaningless [UNK] tokens.

Thus, we propose making use of FastText embeddings rather than word-level tokens. FastText learns subword embeddings, looking at character n-grams rather than the word as a whole. Thus, with FastText, we can provide embeddings even for words from different languages (albeit not likely to be meaningful embeddings).

Existing French / German datasets typically revolve around hate speech detection or sentiment analysis, binary or slightly larger classification tasks. The Real-world Annotated Few Shot Tasks is a few-shot text classification benchmark on a large number of domains in English. To the best of our knowledge there is no multilingual few-shot learning dataset in the same domain. For a streamlined flow consistent across languages, we make use of Project Gutenberg, a free multilingual e-book repository, to create a dataset for author classification for multiple languages.

From Project Gutenberg, we download texts of various popular authors from English, French and German (to name a few - Charles Dickens, H P Lovecraft, Voltaire, Friedrich Nietzsche). The texts are segmented into chunks of ten sentences labeled with the author’s name. Then we follow the methodology proposed by STARTUP for our experiments on both French and German to English. In the case of Fr->En:

- The teacher model is trained on processed French author data in a standard supervised learning task.

- The French teacher is used to pseudolabel the unlabeled data from the English corpus.

- A Fr->En student model is learnt using the aforementioned loss function.

The evaluation process for STARTUP is straightforward. The student model is frozen and a linear classifier is trained on top of it using the support set, as is common in Few-shot learning. As a baseline method, we also consider Naive Transfer, where a linear classifier is learnt on a model trained on the base dataset itself. The simplest form of transfer learning, and yet it performs very well, as shown in the paper. In our case, Naive Transfer is equivalent to evaluating using the teacher model, rather than the student model.

Results

Below are the results for 5-way 15-shot classification:

| Base Language | n_base | Naive Transfer (acc - %) | STARTUP (acc - %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fr | 5 | 20.4 | 20.4 |

| Fr | 10 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| De | 5 | 25.2 | 26.4 |

| De | 10 | 22.8 | 26.4 |

As can be seen from the above table, results across the table are poor, being close to the expected accuracy for a random predictor (20% on a 5-way classification task).

Unfortunately, our experiments were limited by lack of computational resources. As such, both the training time and the amount of data collected were reduced in comparison to the paper. Finetuning FastText embeddings in particular was computationally expensive and reduced the amount of data that was feasible to use. It is our belief that stronger results could be achieved with larger amounts of data and more training time using STARTUP.

Experiments with changing the $n_{base}/n_{target}$ ratio were inconclusive. Changing $n_base$ from 5 to 10 while holding $n_target$ at 5 caused either minor or no changes in all cases except in Naive Transfer for De->En where accuracy drops from 25.2% to 22.8%. Interestingly, the accuracy for STARTUP remains constant at 26.4%.

We do see a marked increase in accuracy when comparing Fr->En and De->En however. In line with our hypothesis - because German and English are closer to each other, transfer should be more efficient - we see stronger performance of both Naive Transfer and STARTUP when doing a cross-domain transfer from German to English.

Conclusion

This post examines Self-training For Few-shot Transfer Across Extreme Task Differences or STARTUP, presented at ICLR 2021. STARTUP is a method proposed for the challenging task of cross-domain few shot learning. Briefly summarized, STARTUP extracts meaning from how the target domain data is distributed among the classes in the base domain, and utilizes this to transfer to the target domain more effectively.

This post also presents FrLove, an attempt to verify whether the distance between languages as measured in a family tree correlates to effectiveness of transfer. According to our preliminary experiments, a “Frenchman” (Fr->En student model) would not be able to identify Lovecraft among his fellow English authors, but a German has a better chance of doing so. However, these experiments are preliminary and our results are inconclusive, given the small amount of training data and training time.

Cross-Domain Few Shot Learning is an interesting and challenging problem, with important ramifications across domains. In the context of language, it opens up new avenues in working with low resource languages, where data is not present in sufficient quantities to enable traditional machine learning methods. Insights on how the model’s parameters change when learning might also prove useful in our own endeavours at learning new languages! It is an exciting problem to say the least, and one to keep an eye on.